Defining Hip Hop Activism

_______________________________________________________________________________

By: Anthony J. Nocella II, Ph.D.

Hip hop is one of the fastest growing youth cultures in the world, as shown by its recent corporatization within the entertainment industry (Fernandes, 2011). Ogbar (2007), author of “Hip-Hop Revolution: The Culture and Politics of Rap,” writes,

The international manifestations of hip-hop are considerable. In the last decade, hip-hop expanded its appeal considerably, there have emerged local communities of ‘head’ in the far reaches of the world. Ghanaian hip-life, Panamanian- and Puerto Rican-inspired reggaeton, South African Kwaito, and other hip-hop/local hybrids have made indelible marks on glocal (global/local) youth culture and political expressions. (p. 180)

For mainstream audiences, hip hop is synonymous with rap, a musical genre that the police, corporate media, and suburban white-middle class often connect with violence, gang activity, and other deviant, nihilistic behaviors. Such assumptions are similar to the stigmatization of other aspects of Black culture throughout U.S. history (Rose, 2008; Watkins, 2005). Hip hop is unfairly generalized because of the media’s tendency to promote rappers whose lyrics are insensitive to women and the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender/sexual, queer, intersexual, and asexual (LGBTQIA) community while exalting the “gangsta” lifestyle (Parmar, Nocella, Shykeem, 2011, p. 288).

In contrast, hip hop culture is founded in African tribal musical customs and emerges out of the U.S. Civil Rights movement (Chang, 2005; Boyd, 2003). Once Africans were brought to the U.S. as slaves, Marshall (2000) explains that “African-American expressive cultures, especially musical ones, have provided opportunities for resistance, critique, and education since their first syncretic soundings sometime in the sixteenth century” (para. 1). Non-corporate modern hip hop continues to exemplify “resistance, critique, and education” (Marshall, 2000, para. 1). Forman (2007) notes that rap and hip hop emerged in the late 1970s and early 1980s within the Black community in the boroughs of New York City not as a call for violence from gang-infested streets, but as a musical genre that hoped to “challenge or disrupt the cultural dominant” through a “combination of defensiveness and willful optimism” (p. 9). Despite this inspiring definition, hip hop still gets regularly stigmatized as violent and misogynistic, sometimes with good cause, as many rap lyrics refer to woman as “hos” and “b-word,” thus perpetuating misogyny and patriarchy. But these negative messages of some rap lyrics are far fewer than those wider-reaching messages of the dominant white, capitalist, colonized, U.S. imperialist culture that promotes patriarchy, sexism and homophobia via all forms of media, only one of which is corporate hip hop (Rose, 1994; Perry, 2005; Williams, 2010). The civilization arising from white European origins argues for competition, control, and normalcy, not for collaboration, interdependence, respect for difference, and equity. However, the latter, positive attributes are celebrated by many communities of color, such as non-corporate hip hop.

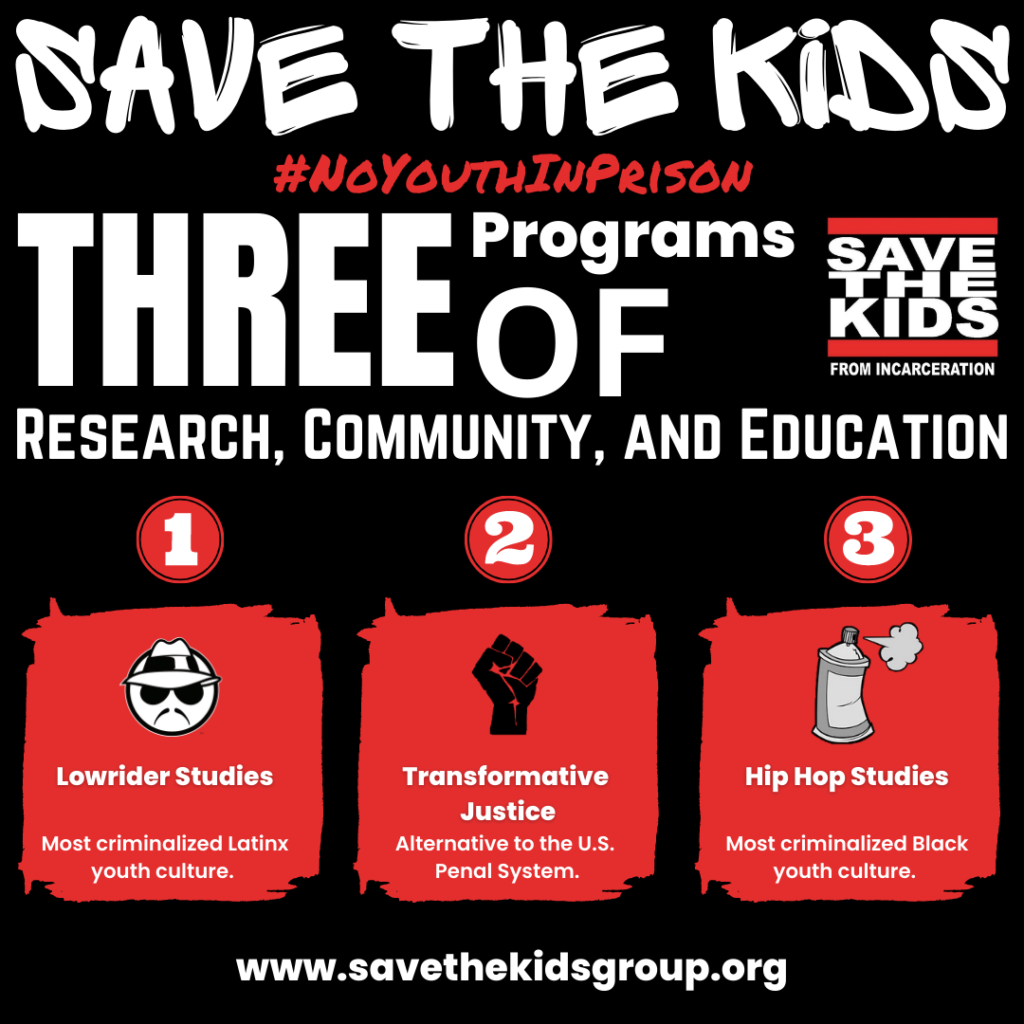

Indeed, non-corporatized hip hop is the only culture that speaks to educating youth of color on a deeper level than merely imparting their pre-slavery and colonialist histories to them (Ball, 2011). Williams (2010) emphasizes the potential power of this “counterhegemonic spirit of hip-hop such as narration of institutionalized racism, internal colonialism, underclass entrapment, and urban poverty, to help explain the external sources of prevalent psychosocial problems among African American youth” (p. 230). Hip hop speaks to the current conditions of poor urban communities, writing and rapping on topics from police brutality to the war on drugs. Hip hop—through graffiti, dance, rap, fashion, education, deejaying, beat boxing, and locally owned private businesses—tells the story of a people who must now rebuild their communities after periods of slavery, colonization, Jim Crow, the Civil Rights era and continued institutionalized racism. Part of this rebuilding is to offer what Marshall (2000) calls “an alternative education—a challenge to dominant notions of knowledge and truth” that youth find in traditional Western-Colonial schooling (para. 4), noting that early hip hop artists and producers, such as KRS-One, actually referred to their art as “‘Edutainment’” (para. 4.). Hip hop is comprised of artists using their medium to identify and criticize social ills while offering alternatives for the oppressed. In his song “Hip Hop Lives,” KRS-One (2007) defines the genre as “more than music”; rather, it is “knowledge,” and an “intelligent,” “relevant movement.” Hip hop, as KRS-One defines it, is about positive and intellectual momentum and is, from its earliest inceptions, a social justice movement with which its listeners became engaged advocates rather than passive listeners (Parmar, 2009). (Nocella and Socha, 2013)

Hip Hop culture has four traditional agreed upon elements graffiti, emcee, DJ, and breakdance. These elements are transferred into Hip Hop activism as (1) reclaiming space, (2) art, (3) making noise and beats, and (4) speaking out.d beats, and (4) speaking out.